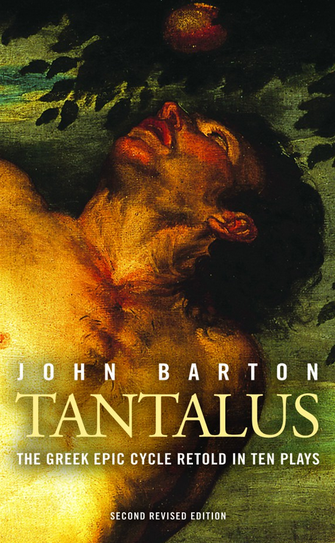

TANTALUS

by John Barton

(Founder-director, Royal Shakespeare Company)

Edited by Oliver Soden

Foreward by Sir Trevor Nunn

and with an introduction by Paul Cartledge

Oberon Books, 2014

Paperback, £18.99; 512 pages

Buy book

Who is to Blame? What is the Truth? Could it be Otherwise?

When theatre began, two and a half millennia ago in ancient Greece, it drew from a well of even older myths, the Great Epic Cycle. Stories and characters from the beginning of our imagination inspired John Barton to write the great cycle of human life Tantalus, an epic theatre myth for the new millennium. Its subject is the Trojan War, a crusade which becomes a catastrophe. Heroes humbled, children hurt, mothers and fathers bereaved, entire nations shaken and rebuilt: all pass through this kaleidoscope of human fate. This new, revised and streamlined edition of Tantalus is the culmination of a life-time's work.

by John Barton

(Founder-director, Royal Shakespeare Company)

Edited by Oliver Soden

Foreward by Sir Trevor Nunn

and with an introduction by Paul Cartledge

Oberon Books, 2014

Paperback, £18.99; 512 pages

Buy book

Who is to Blame? What is the Truth? Could it be Otherwise?

When theatre began, two and a half millennia ago in ancient Greece, it drew from a well of even older myths, the Great Epic Cycle. Stories and characters from the beginning of our imagination inspired John Barton to write the great cycle of human life Tantalus, an epic theatre myth for the new millennium. Its subject is the Trojan War, a crusade which becomes a catastrophe. Heroes humbled, children hurt, mothers and fathers bereaved, entire nations shaken and rebuilt: all pass through this kaleidoscope of human fate. This new, revised and streamlined edition of Tantalus is the culmination of a life-time's work.

Working for John Barton...

My first job after graduating, one of rare and frustrating privilege, was to work for one of the founder-directors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, John Barton (1928-2018), as a kind of literary assistant. He was frail, and his life had shrunk to a series of doctors' appointments and the odd masterclass, enabled by the devoted trio of his carer (Eva), his PA (Sue Powell), and his sister (Jennifer). But he was determined to publish a third and final version of his ten-play series, Tantalus, which put theatrical flesh on the fragmented bones of the Ancient Greek poems known as the Epic Cycle.

First written for the Royal Shakespeare Company's millennium celebrations, and given a lavish and expensive first production that stretched across a day and was staged in Colorado and in Stratford, the plays had had a troubled birth. Another edition, laying out a definitive text on John's own terms, was a way of putting various quarrels to rest. The premiere led to the breakdown of his life's friendship with its director, Peter Hall, and John's obituaries documented his anger at the major cuts that Hall had implemented. True, but his lasting rage was at Hall's breaking a promise not to put masks on the actors. In the event, our work on a final version of Tantalus took some years, during which time, a decade on from the millennial quarrels, the two of them had a wary peace-making meal at a local restaurant. John was losing his body but not his mind; Peter Hall was starting to lose both. The lion and the unicorn of British theatre metaphorically circled one another around the Villandry table, their lustre fading, their hot blood cooling. They were, almost, mellow.

Anyone who visited John's flat will remember how the walls were lined with thousands of black folders containing his scripts and correspondence, a legendary career preserved in a million sheets of dusty paper. To and fro the endless black folders would go between us, John implementing revisions, me peering through a magnifying glass in an attempt to read his hieroglyphs: frailty had shrunk his already small handwriting into faint and illegible squiggles. I remember arriving at his flat on the day I thought the manuscript had finally, finally, been finished. And I remember my heart sinking on hearing him say "there's just one bit I'd like to change...". Did he want to reinstate the opening speech, which went in, and then went out again, almost daily? "It's the scene", he continued, "between Lancelot and Guinivere...". A decade's work on Tantalus finished, John had simply hopped nimbly from one mythology to another, moving on to an adaptation of his beloved Thomas Malory without a second thought.

All this work on the Greeks meant that I never really saw, as others did, the ease with which he could swim about in Shakespeare. One of his party tricks was to be thrown a quotation, from Hamlet say, and to fire back not just the act and scene, but the line number as well. He and his wife, the scholar Anne Barton, would apparently while away long car journeys by batting all one hundred and fifty-four sonnets back and forth to one another from memory, as others might play I Spy. Anne, from whom he had separated but to whom he spoke most days on the telephone, died slowly over the summer of 2013, and the final edition of Tantalus, when it at last appeared the following year, was dedicated to her memory – with a certain sly and loving irony on John's part, I thought, as Anne had had limited affection for the project.

It was Anne's memorial service, in Cambridge, that produced my most vivid memory of John. In poor health and exhausted by the journey from London, he was nevertheless determined to deliver Prospero's speech from Act V of The Tempest: "Ye elves of hills, brooks...". He was wheeled to the lectern, refusing a microphone, disdaining a large-print copy of the text, and forgetting his spectacles. His voice quickly remembered how to project, but the text, in his lap but no longer in his head, was all but unreadable without his glasses. He then proceeded to deliver the speech. The scansion was faultless, the imagery mesmeric, and the resemblance to what Shakespeare had written often slight. Where memory had failed, he had simply improvised, effortlessly unspooling ribbons of blank verse. Even when lost in the thickets of old age, John would melt into lucidity at any mention of Shakespeare's words, which ran in his veins like red blood cells carrying literary oxygen.

I do remember his saying that if I could do anything for him, it would be to scotch the famous rumour that he chewed razor blades for recreation. The blades littered his desk, it is true, to enable him, for whom technology was a foreign land, to cut and paste chunks of his script. But memories of a single demonstration, in which he was trying to prove (God knows why) that one could hold blades in the mouth without being cut, had got out of hand. So he said.

John could be confused and confusing in the too-long decline of his last years, but intimations of who he had been bubbled frequently to the surface. And he was, always, kind. We published a version of Tantalus at last. But how could a key to all mythologies ever really be finished? John was less interested in definitive answers than in continually asking difficult questions, as in his probing refrain, for Tantalus:

Who is to Blame?

What is the Truth?

Could it be Otherwise?

Oliver Soden, January 2018.

My first job after graduating, one of rare and frustrating privilege, was to work for one of the founder-directors of the Royal Shakespeare Company, John Barton (1928-2018), as a kind of literary assistant. He was frail, and his life had shrunk to a series of doctors' appointments and the odd masterclass, enabled by the devoted trio of his carer (Eva), his PA (Sue Powell), and his sister (Jennifer). But he was determined to publish a third and final version of his ten-play series, Tantalus, which put theatrical flesh on the fragmented bones of the Ancient Greek poems known as the Epic Cycle.

First written for the Royal Shakespeare Company's millennium celebrations, and given a lavish and expensive first production that stretched across a day and was staged in Colorado and in Stratford, the plays had had a troubled birth. Another edition, laying out a definitive text on John's own terms, was a way of putting various quarrels to rest. The premiere led to the breakdown of his life's friendship with its director, Peter Hall, and John's obituaries documented his anger at the major cuts that Hall had implemented. True, but his lasting rage was at Hall's breaking a promise not to put masks on the actors. In the event, our work on a final version of Tantalus took some years, during which time, a decade on from the millennial quarrels, the two of them had a wary peace-making meal at a local restaurant. John was losing his body but not his mind; Peter Hall was starting to lose both. The lion and the unicorn of British theatre metaphorically circled one another around the Villandry table, their lustre fading, their hot blood cooling. They were, almost, mellow.

Anyone who visited John's flat will remember how the walls were lined with thousands of black folders containing his scripts and correspondence, a legendary career preserved in a million sheets of dusty paper. To and fro the endless black folders would go between us, John implementing revisions, me peering through a magnifying glass in an attempt to read his hieroglyphs: frailty had shrunk his already small handwriting into faint and illegible squiggles. I remember arriving at his flat on the day I thought the manuscript had finally, finally, been finished. And I remember my heart sinking on hearing him say "there's just one bit I'd like to change...". Did he want to reinstate the opening speech, which went in, and then went out again, almost daily? "It's the scene", he continued, "between Lancelot and Guinivere...". A decade's work on Tantalus finished, John had simply hopped nimbly from one mythology to another, moving on to an adaptation of his beloved Thomas Malory without a second thought.

All this work on the Greeks meant that I never really saw, as others did, the ease with which he could swim about in Shakespeare. One of his party tricks was to be thrown a quotation, from Hamlet say, and to fire back not just the act and scene, but the line number as well. He and his wife, the scholar Anne Barton, would apparently while away long car journeys by batting all one hundred and fifty-four sonnets back and forth to one another from memory, as others might play I Spy. Anne, from whom he had separated but to whom he spoke most days on the telephone, died slowly over the summer of 2013, and the final edition of Tantalus, when it at last appeared the following year, was dedicated to her memory – with a certain sly and loving irony on John's part, I thought, as Anne had had limited affection for the project.

It was Anne's memorial service, in Cambridge, that produced my most vivid memory of John. In poor health and exhausted by the journey from London, he was nevertheless determined to deliver Prospero's speech from Act V of The Tempest: "Ye elves of hills, brooks...". He was wheeled to the lectern, refusing a microphone, disdaining a large-print copy of the text, and forgetting his spectacles. His voice quickly remembered how to project, but the text, in his lap but no longer in his head, was all but unreadable without his glasses. He then proceeded to deliver the speech. The scansion was faultless, the imagery mesmeric, and the resemblance to what Shakespeare had written often slight. Where memory had failed, he had simply improvised, effortlessly unspooling ribbons of blank verse. Even when lost in the thickets of old age, John would melt into lucidity at any mention of Shakespeare's words, which ran in his veins like red blood cells carrying literary oxygen.

I do remember his saying that if I could do anything for him, it would be to scotch the famous rumour that he chewed razor blades for recreation. The blades littered his desk, it is true, to enable him, for whom technology was a foreign land, to cut and paste chunks of his script. But memories of a single demonstration, in which he was trying to prove (God knows why) that one could hold blades in the mouth without being cut, had got out of hand. So he said.

John could be confused and confusing in the too-long decline of his last years, but intimations of who he had been bubbled frequently to the surface. And he was, always, kind. We published a version of Tantalus at last. But how could a key to all mythologies ever really be finished? John was less interested in definitive answers than in continually asking difficult questions, as in his probing refrain, for Tantalus:

Who is to Blame?

What is the Truth?

Could it be Otherwise?

Oliver Soden, January 2018.